Editor’s Note: Following the World Series, Peter J. Wallace e-mailed me to pitch a Clayton Kershaw article, and so please welcome him to Dodgers Digest as a guest writer.

I think it serves as a great reflection on just how ridiculous Clayton’s career with the Dodgers was and is a great tribute to an all-time great player we’ve been lucky enough to witness on our favorite team.

======

I am one of those children who fell asleep listening to Vin Scully on my transistor radio in the late 1970s. I later became a historian — but the first evidence of my future path came from the fact that I became a Brooklyn Dodgers fan in the 1980s, devouring everything I could find (before the internet existed) about Dodger history. During those years, I was fascinated by the life and legacy of Sandy Koufax — and tried my best to show that he was the greatest pitcher ever (at least during his peak years). My Giants’ fan older brother was having none of it.

I spent my early adult years pursuing my doctorate and becoming a pastor — and quite frankly, the Dodgers weren’t exactly doing much after Gibby’s blast in ’88 to keep my attention. But in the early 2010s I couldn’t help but notice that a young Clayton Kershaw had reached Koufax-esque numbers without the long sojourn in the wilderness that kept Sandy from GOAT-ness. On June 28, 2014, I noticed in the box-score that Kershaw had made it through four perfect innings. I watched the rest of the game. It was entirely fitting that the same Miguel Rojas who saved Kershaw’s no-hitter was the same Miggy Ro who sent Kershaw out as a World Champ 11 years later.

But whereas my efforts to prove that Koufax was the greatest could never quite convince my historian self, as I continued to delve into the stats, it became clear to me that there was a case to be made that Clayton Kershaw is the greatest pitcher of all time.

——

First of all, I recognize the first rebuttal detractors will use despite everything else written in this piece, which is that unlike Bob Gibson, Christy Mathewson, and especially Sandy Koufax, his elite run prevention was not taken to another level in the postseason. But he did have his share of great playoff moments — including leading the Dodgers in cWPA in the 2020 World Series — had a postseason narrative inflection point happen at the hands of a team that was cheating in 2017, and ended up going out a three-time champ while some of his closest comps haven’t exactly killed it over a large sample either. Additionally, it’s quite fitting that in the 12th inning of Game 3 of the 2025 World Series, when the bases were loaded, manager Dave Roberts called on Kershaw to get that one out, and that one batter was important enough to end up giving him the fifth-highest cWPA among pitchers in this World Series. In the end, the final pitch of Clayton Kershaw’s career did one last time what he had done better than any other starter in Major League history.

That’s a theme, as I take it that the purpose of the pitcher is to prevent runs from scoring. Everything else is subordinate to this goal. There may be value in being the Strikeout King (obviously, if you strike everyone out, no one will score!), but while Nolan Ryan has the remarkable and amazing description of being the undisputed Strikeout King, I doubt that there are many who would say that he was the Greatest Pitcher of All Time. Anything to do with K-rate is overpopulated with modern pitchers and devalues the old-timers. On the other hand, other metrics overvalue the dead-ball era. Another example of a less than helpful stat for our purposes is FIP (Fielding Independent Pitching). FIP is useful for comparing pitchers against others of their own era, but the paucity of home runs prior to 1920 means that dead-ball era pitchers are over-represented on that leader board. Likewise raw WAR will over-value the workhorses of prior generations — simply because they pitched so much. While there is undoubtedly tremendous value in pitchers who could pitch complete games every four days, if the question is, “Who was the best pitcher at preventing runs from scoring?” WAR will not help you understand that.

——

In order to compare pitchers from different generations, we need a leader board that provides a healthy sample of pitchers from across generations. Since I think that preventing runs from scoring is the pitcher’s chief objective, I am generally interested in any metric that looks at that.

In terms of ERA+ (ERA adjusted to player’s era and ballpark), Kershaw has a very good claim to be the GOAT starting pitcher. Among pitchers with 2,000 IP, he is tied for first with Pedro Martinez. ERA is mildly interesting, but the leaderboard skews towards the dead-ball era. ERA+ is better, because it adjusts to the league averages, and so can be used to compare across generations.

There are two more recent metrics that are also useful (but we don’t have the data for old-timers yet):

Base-Out Wins Saved (base-out wins saved) – called REW (since it converts run expectancy into wins) – measures the wins above average the player was worth by looking at the 24 base-out situations.

Situational Wins (WPA/LI) (win probability added divided by leverage index) “captures the change in win expectancy from one plate appearance to the next and credits or debits the player based on how much their action increased their team’s odds of winning.”

I use these metrics because my argument is that Kershaw is the greatest pitcher of all time at preventing runs from scoring.

To be clear, I acknowledge that others could make a case for other starting pitchers on other grounds. Kershaw’s decision to retire before he completely fell apart preserved his numbers at a place where other pitchers had been before their late-career demise. So, for instance, if Lefty Grove had retired after the 1939 season, he would have had an ERA+ of 153. But he pitched two more years. Or if Walter Johnson had retired after 1925 (at 37 – the same age as Kershaw) he also would have had an ERA+ of 154. But as this essay will suggest, the defining characteristic of Clayton Kershaw’s pitching genius was his elite ability to prevent runs from scoring long after his “stuff” was no longer elite, regardless.

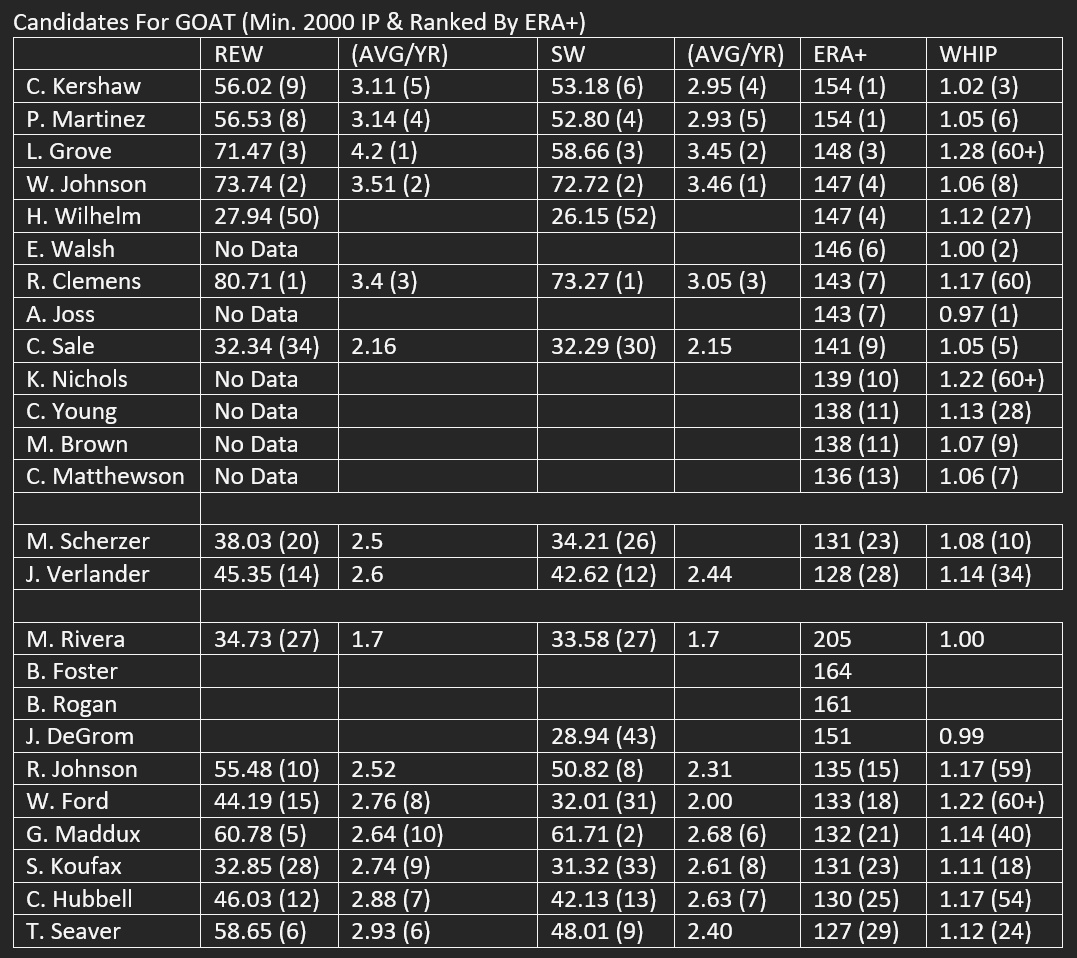

Candidates for GOAT (minimum of 2000 IP) ranked by ERA+

Note: Yes, I realize that Hoyt Wilhelm was a relief pitcher… but he did have the requisite IP, so I didn’t want to omit his name.]

——

The Greatest of His Generation (GOG)

I confess that it irks me when I read baseball writers suggest that Justin Verlander or Max Scherzer are in the same ballpark with Kershaw – or might be in the conversation for the best pitcher of this generation (Chris Sale and Jacob DeGrom are also sometimes mentioned – but while they certain deserve consideration to be compared with Verlander and Scherzer – when it comes to GOG they are “honorable mentions.” Kershaw has been the current leader in APW, WPA/LI, REW, since 2015 – ERA+ since 2014, and RE24 since 2016. Verlander is ahead of him in WAR simply because he is older and healthier (and counting stats will favor pure longevity), and DeGrom passed him in WHIP in 2022, but Kershaw has always lapped the field in effectiveness.

I also find it really ironic that everyone treated Kershaw as if he was washed up ever since 2018. While Verlander and Scherzer were slightly better from 2018-2022, Kershaw sustained his value better to the end.

Scherzer or Verlander were slightly better during 2018-2022, but not by much – and during his last three years, Kershaw significantly out-performed them. Obviously, Kershaw’s last three years were just “good” – but when a player is past his prime and he is still pitches nearly 40% better than average – that’s crazy. Verlander and Scherzer are properly said to be league average, by comparison.

All were similar workhorses on an innings per start basis for their careers, but Kershaw does lack the bulk of innings due to injuries. That said, I don’t think it diminishes his greatness that injuries cut his prime years short, yet despite that he was still significantly more effective at run prevention than his contemporaries even later into their respective careers.

——

Greatest of All Time

So having put to rest the idea that any other pitcher of his own generation compares to Clayton Kershaw, let’s look at some comparisons to other claimants to the GOAT.

Clayton Kershaw only had five seasons where his ERA was above 3:

2008 – 4.26 (rookie year – 107.2 IP)

2019 – 3.03 (that’s right – a decade in between mortal years…)

2021 – 3.55

2024 – 4.50 (seven starts – injured)

2025 – 3.36

But in between those “mortal” years, he was almost in prime form:

2020 – 2.16 – only 8 walks in 10 starts [ERA+ of 202!!]

2022 – 2.28 in 22 starts

2023 – 2.46 in 24 starts

How does this compare to other generations?

ERA+ generally has the disadvantage of privileging pitchers who pitched in the dead-ball era (where unearned runs were far more common). The fact that Kershaw still leads in ERA+ is remarkable. But other metrics can measure run prevention better.

Base-out runs saved (RE24) measures how a player performs given the 24 different base-out states (zero, one, or two outs – and the eight different baserunner arrangements: empty, first, first and second, first and third, second, second and third, third, and bases loaded). Run expectancy tells you the number of expected runs – and how a pitcher performs relative to that expected number gives you his RE24. It’s all nice and good to say that the pitcher didn’t deserve the run (and so he keeps a good ERA), but if he allows those unearned runs to score, you are still going to lose the game!

Now, here is the leaderboard for career RE24:

I’ll stop there — because there is no one below this who comes anywhere close to these numbers (#11 is at 432.338). RE24 is a cumulative stat — so it favors those who pitch more. But look at the per inning RE24. Pedro Martinez and Lefty Grove are the only pitchers who did better at run prevention (and Roger Clemens is the only other pitcher who comes even vaguely close). Of those pitchers who reached 2,000 innings, there are three who stand out.

Pedro Martinez

Pedro Martinez is easily the most comparable to Kershaw – not least because they both retired at age 37 and had very similar number of innings pitched. Let’s start with their peaks:

It is safe to say that Pedro Martinez has the edge for peak performance.

The career numbers show a very balanced story:

Kershaw has the edge in ERA, but the difference in offenses render that advantage nugatory (hence the identical ERA+). Martinez has the lead in WAR, but he had twice as many complete games due to the tendency in his era for managers to leave starters in the game longer. Pedro’s peak was astounding – but Kershaw’s ability to maintain elite run prevention throughout the rest of his career is what gives him the edge. Look particularly at the last five years of their careers:

These years show the difference. Pedro had a 3.86 ERA over the last five years of his career (with a WHIP of 1.18, and an ERA+ of 109 – total WAR of 8.8). Kershaw’s last five years (definitely the worst five year stretch of his career) saw a 2.98 ERA with a WHIP of 1.08 and ERA+ of 140 – and total WAR of 10.9. Since they both retired at age 37, this is very much an apples-to-apples comparison.

In his 18 years, Kershaw had a ERA+ of 170 or better eight times. Pedro Martinez did it six times (though he had five seasons over 200, where Clayton only did that twice). In other words, Pedro had a seven year peak from 1997-2003 that was unreal – but he also had five years with an ERA above 3.50). As noted above, Clayton only had three such years (including the one with 7 starts). Kershaw maintained his elite run prevention to the point where, as Alden Gonzales noted on ESPN.com recently, “Kershaw’s stuff was no longer even good enough to be drafted as an amateur, and yet he was rolling through some of the best competition in the world.”

Walter Johnson

What about earlier generations? As previously said, ERA+ provides a useful metric for evaluating pitchers across generations. Among starting pitchers with over 2,000 innings pitched, Lefty Grove (148) and Walter Johnson (147) are the closest to Kershaw and Martinez. Ed Walsh (146) and Addie Joss (143) come next among starters (though Hoyt Wilhelm combined starting and relieving – and came in at 147).

Walter Johnson had an ERA+ over 170 seven times (four times over 200) — but his ERA was so low because he generally allowed 30-50 unearned runs per year (even factoring in innings, it’s an outsized number due to the way scoring has evolved)! Lefty Grove had an ERA+ over 170 five times (1930-31, 1935-36, and 1939) – and generally gave up 15-20 unearned runs per year. (In comparison, Pedro never gave up more than twelve unearned runs – Kershaw never gave up more than seven…). So for instance, Johnson’s runs per 9 is 2.89 (at a time when his opponents generally scored 4.23 runs per game), while Kershaw gave up 2.78 runs per 9 (when his opponents generally scored 4.37 runs per game). Pedro was 3.20 (against 4.91). Lefty Grove was 3.64 (against 5.15). Expressed as a ratio (where lower is better), their career ratios are as follows:

Grove .70

Johnson .68

Martinez .65

Kershaw .64

One way to think about this ratio is to say that where their opposing teams generally scored one run, Kershaw only allowed .64 runs.

In order to not prejudice the case by cherry-picking the number of seasons that shows off Kershaw at his best, we will take Walter Johnson’s epic 8-year peak (1912-1919):

The sheer volume of Johnson’s production is overwhelming, and the quality is undeniable. But Johnson gave up a ton of unearned runs, likely due to the aforementioned way scoring has changed. Look instead at runs per 9 innings (RA9). Where Johnson allows 2.20 runs per 9 against his opponents’ habit of scoring 3.94 per 9 (a ratio of .56), Kershaw has 2.43 against 4.26 (a ratio of .57). In other words, despite all the differences in their eras, their run-prevention is virtually identical. Kershaw has better strikeout numbers (both absolute and rates), while Johnson dominates the number of innings pitched (and complete games — and shutouts).

Once again, Kershaw’s true greatness was revealed in his post-prime years. Look at their last five years:

Johnson still maintained remarkable production (double the IP and WPA, nearly double the WAR and RE24), but Kershaw’s elite run prevention again stands out. To use our ratio of runs allowed per 9 vs. the opponents’ normal runs per 9, Johnson was at .79, while Kershaw was slightly better at .73.

Lefty Grove

Only one left-hander vies with Kershaw for the title of GOAT (if you agree that the chief object of a pitcher is to prevent runs from scoring). It is likely that Lefty Grove has suffered from the fact that his career coincided with the rise of the home run, and so the late 1920s and early 1930s was a hitter’s paradise. His career ERA of 3.06 does not look that impressive — until you realize that teams were scoring 5.3 runs per game during his career (Walter Johnson’s lifetime 2.17 ERA came at a time when teams scored 4.09 runs per game). But Lefty Grove continued the older workhorse tradition. At his peak in the early 1930s he would throw 27 complete games — and then also come in as the closer in 10-15 games per year (leading the league in saves with 9 in 1930). Undoubtedly this boosted his leverage stats! Grove led the league in WAR eight times from 1928-1937, ERA nine times from 1926-1939, strikeouts in seven consecutive seasons from 1925-1931, and RE24 eight times from 1928-1936 (omitting simply the injury year of 1934). His 82.7 Win Probability Added is the highest career mark in baseball history.

The challenge with a statistical analysis of Grove’s career is the blip of 1934, when an arm injury left him with a 6.50 ERA over 109 innings – and therefore drags down any range of his “peak” years, so we will evaluate two five-year peaks and contrast it with Kershaw’s best ten-year stretch.

As with Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove plainly dominates the bulk stats. He pitched a lot more. But like with Johnson, his ERA+ advantage is neutralized by the RA9 ratio: .61 to Kershaw’s .59. So again, their peaks come down to a debate over the volume of an early 20th century workhorse versus the strikeout mastery of a 21st century legend.

The only blemishes on Lefty Grove’s career are his rookie year in 1925 (like Kershaw), an injury ravaged year in 1934, and the last two years of his career (ages 40-41). He had ten years over 140 ERA+ (Kershaw had 11 such years). The difference is that Kershaw came back from his injury ravaged year to post a 124 ERA+ in his final year — while Grove lingered for a couple years, dropping from 185 in 1939 to 112 in 1940 to 95 in 1941.

The other way of putting it is that Grove was arguably the best pitcher in baseball from 1926-1939 (with the obvious exception of 1934), leading the league in either WAR, wins, ERA, or strikeouts in every year! But all this does is demonstrate that Lefty Grove was the clear GOG, and puts him into contention for the GOAT.

I think that my analysis suggests that this comparison could go either way, and you won’t offend me if you say that you prefer Grove’s bulk stats. But I think that Kershaw’s elite total run prevention — even as his “stuff” was diminishing — pushes him over the top.

Roger Clemens

The final contestant who deserves discussion is Roger Clemens. His legacy is deservedly murky, due to the PED controversy — but his performance record is also a bit murky. After his obligatory introductory period (1984-85), he rattled off an impressive streak of 7 years of dominance, followed by four years of uneven performance. When he left Boston, he had two brilliant years in Toronto (1997-98), followed by five years of mediocrity in New York, before turning in three years of genius in Houston, and then ending with a whimper in pinstripes at age 44. His thirteen years in Boston (3.06) were bested by his three in Houston (2.40) and his two in Toronto (2.33), but his Yankee tenure ruins his claim to be the GOAT (4.01 in six seasons).

In fact, the comparison that dooms Clemens is not Kershaw, but his contemporary: Pedro Martinez.

Clemens’ RE24 is the best in baseball history, which means that he cannot be ignored in any conversation about the GOAT. He had twelve seasons above 140 ERA+ (out of 24 big league seasons) – and impressively, besides his rookie year, he was never below 100. His best years were scattered across three decades (winning seven Cy Young awards in 1986, 1987, 1991, 1997, 1998, 2001, and 2004). But he was not even the GOG. In the early ‘90s it looked like he would reach that pinnacle – but then Pedro Martinez launched his incredible peak from 1997-2003. What gives Clemens his claim to greatness is his longevity – and the problem is that PED’s enabled him to do that.

But even a careful look at the numbers will show that Clemens did not achieve the highest rank of run-prevention. His RA9 vs. opponents expectations (.72) falls short of Walter Johnson (.68) and Pedro Martinez (.65), who both still trail Kershaw (.64).

——

When it comes to run prevention, I believe no starting pitcher in Major League Baseball history has been better than Clayton Kershaw, especially so after drilling deep into the context surrounding their performances. And since the pitcher’s chief object is to prevent runs, it is entirely reasonable to argue that Clayton Kershaw is in fact the GOAT (or if not that, at least the greatest at run prevention).

======

Peter Wallace (Ph.D. in history from the University of Notre Dame) is a life-long Dodger fan, and the pastor of Michiana Covenant Presbyterian Church in Granger, Indiana. He is not on social media*, but his email address is his first name at whole name dot org.

*Editor’s Note: Smarter than me.